The decolonization of the field of peacebuilding has so far been purely academic. People have critiqued the field, and critiques have also been developed of the critiques; Sabaratnam’s solutions, in ‘Avatars of Eurocentrism in the Critique of the Liberal Peace’, revolve around finding the voice of the subaltern within academia, as well as reducing the epistemological violence against the colonized population. Questions still remain however, about how an average educated Indian would be able to deal with a conflict in a peaceful way, using the western academic field of peacebuilding. The ‘average’ Indian does not know about connectors and dividers; nor are they aware that conflict resolution and peacebuilding are considered different approaches. An ‘average’ Indian, would ask me what I’m studying and a response of “Conflict Transformation!” would leave them disappointed in my parents’ inability to raise a doctor or an engineer; they would further interrogate me about what this field of peacebuilding is.

But all Indians know peacebuilding. They know about Gandhi and his protest methods, and they could give you a detailed and accurate history of exactly how India fought for their Independence, down to each individual year that a major event occurred. They are building peace, even when they do not realize it. Practice-based approaches to peacebuilding have been starting to be decolonized, one protest at a time. And thus, I feel the need to account for the novel Indian methods of building peace, using non-violent methods of mobilization. In this regard, I will describe methods of creating a revolution, that the ‘subalterns’ have led, and how these have created a step forward against repressive government policies.

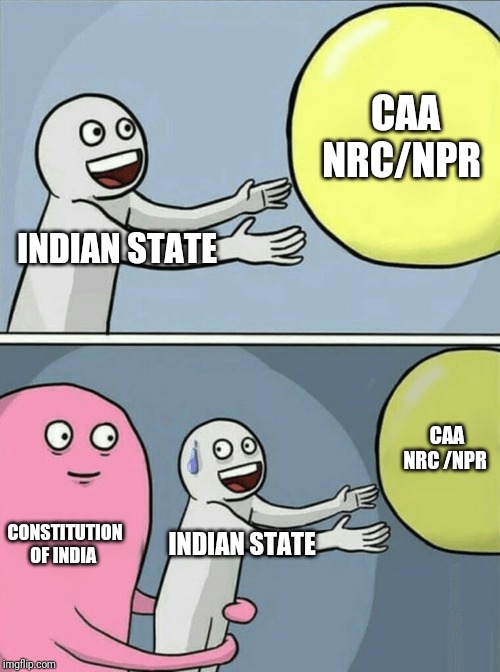

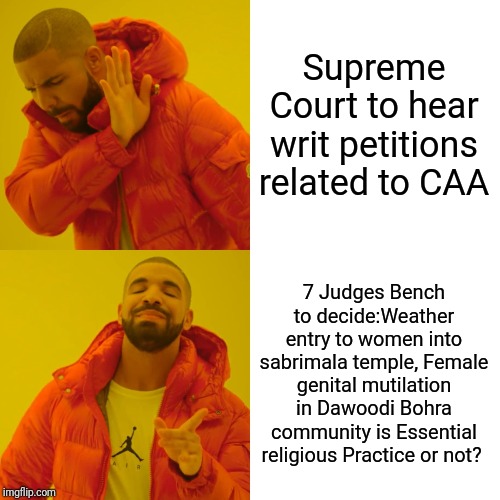

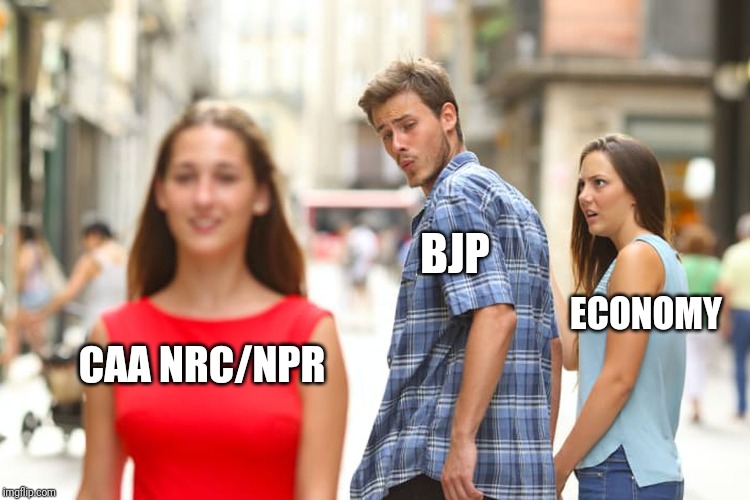

The repressive government policy I refer to here, is that of the “Citizenship Amendment Act” (CAA), and the National Registry of Citizens (NRC) which was passed recently. This policy allows for the creation of a list of individuals who sought refuge in India before 2015, who would be allowed to become citizens of India; but this policy benefits only Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Christian and Parsi refugees from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Amendment leaves out Muslims, as well as refugees such as the Sri Lankan Tamils in India, Rohingyas from Myanmar, and Buddhist refugees from Tibet. This law thus excludes Muslim individuals from becoming citizens of the country, and also acts negatively towards people of a lower socio economic background, who may not be able to produce the necessary documentary proof of citizenship. Thus, protests have erupted across the country, and I feel extremely proud to be able to say that students have been at the forefront of what I will term a ‘revolution’.

I will focus upon five examples of the novel kinds of protests against this act. A disclaimer that I would like to provide regarding these is the fact that I chose these based upon my own understanding of the subject matter having been unable to physically participate, and I am aware that many other kinds of brilliant protests are taking place in India. These five kinds of protests that I have had the pleasure of reading and hearing about are as follows:

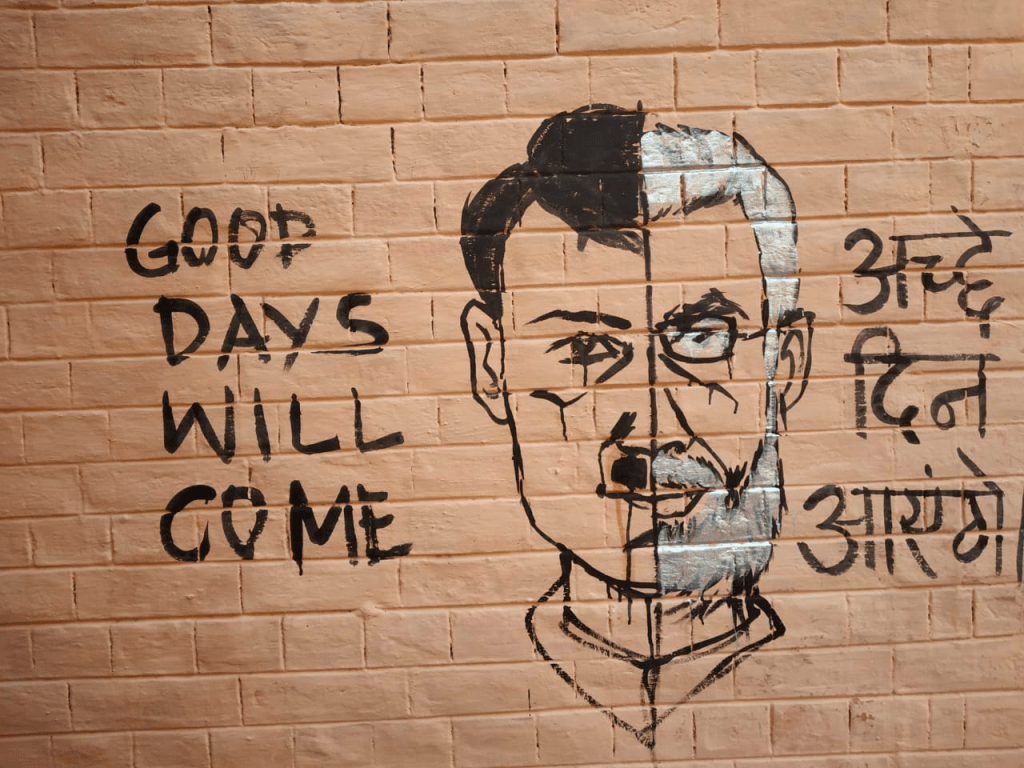

- ‘Read for Revolution’ at Jamia Milia Islamia University (New Delhi): Students and citizens in this Muslim University have come out in large numbers in order to protest against the CAA by sitting in front of the gates of the institution and reading texts, and using art-based approaches such as street painting and other installations. These texts have strong principles of non-violence, ideas of equality and social justice embedded in them; Gandhi, Ambedkar and others are some authors focused upon, and the constitution is also being read and discussed in small groups. There has been a makeshift “library” created in the area, where books are available throughout the day. The primary purpose for this is to show dissent using the Gandhian principles of ‘Satyagraha’, and to spread knowledge and information regarding the political rights enshrined in the constitution of India.

Women’s protest at Shaheen Bagh (New Delhi): Hundreds of women, predominantly muslim, occupied an area in New Delhi called Shaheen Bagh. Since the 15th of December, 2019, these women have staged a sit-in protest to assert their rights. On the 31st of December, 2019, when the temperature dropped down to around three degrees celcius (around 37 degrees fahrenheit) which is unfathomably cold in India, these brave women chanted slogans and were armed with light sweaters and shawls as they also represent the lower socio economic class.The idea of Muslim women from a lower socio economic background represents one of the intersectional identities in India that is treated with the greatest degree of hostility. Indian hospitality was always maintained, and everyone joining them was offered tea and a great conversation.

Student Protests at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), in New Delhi: Students from this university have always been politically active, and they stood up in protest against both the CAA, and the proposed fee hike at the university. This fee hike would mean that a number of students from a lower socioeconomic background would not be able to attend the university. Students bravely decided to not attend any of their scheduled examinations, and gave an ultimatum to the authorities in order to restore their own rights.

Music and Sloganeering in Assam: Since the start of the protests against the imposition of the NRC in Assam, protests have erupted across the state. These have been peaceful, and the Assamese people have used the medium of music and poetry in order to unite the people. One such example is the song by a popular singer-composer Bipin Chawdang, who writes songs like ‘Nagorikotwo Songsudhoni Bidheyok khon nelage’ (We don’t want CAA) and ‘Jatir maatir gaan’ (Song of my people and land) are a rage among anti-CAA protesters. Traditional music, called ‘borgeet’ and ‘naam’ have also been performed at various protest sites.

Social Media Protesting: This method of protest has been used by the youth to spread their message widely, across India. The government resorted to shutting down the internet in many places, including in Assam. This did not mean that the generation of creative memes stopped, and the message of the unfairness of the CAA spread widely because of this.

Gayatri Spivak in her seminal text ‘Can the Subaltern speak?’ writes, “one never encounters the testimony of the women’s voice-consciousness”, at least in historical literature. Today, I take a more optimistic view of the field of peacebuilding, and I say that the testimony of their voice-consciousness is slowly gaining strength. The subaltern are “finding their voice”, as Patricia Hill Collins would describe it, in her text ‘Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory’.

References

Sabaratnam, M. (2013). Avatars of Eurocentrism in the Critique of the Liberal Peace. Security Dialogue, 44(3), 259-278.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak?. Can the subaltern speak? Reflections on the history of an idea, 21-78.

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press.